Contributing to the Greater Good with Colonel Jack Jacobs

The public’s awareness about their role in building a better future has been waning. More and more people are forgetting their civic duty to do something for the greater good despite not wielding political power. Norman Kallen and Stuart Brown sit down with Colonel Jack Jacobs, a Medal of Honor recipient for his service in the Vietnam War, who discusses how to boost public service and encourage people to take action. Breaking down the most important lessons from his storied career, he explains the importance of adhering to the truth despite rampant misinformation and how businesses can balance revenue generation and culture building. Colonel Jacobs also shares insights on resolving the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, as well as the best way to improve the US government’s treatment of veterans.

—

Contributing to the Greater Good with Colonel Jack Jacobs

Introducing Colonel Jack Jacobs

We’re back on Open For Business. I’m here with my partner, Stuart Brown. Our guest is Colonel Jack Jacobs. Colonel Jacobs, welcome to the show. It’s wonderful to have you.

Thanks for having me on the program.

We greatly appreciate it.

Before we get started, it’s an honor to have you. I can’t say enough about thanking you for your service to this country in so many ways. Thank you.

It was an honor to serve. It was interesting that you mentioned the notion of service because everybody says, “Thank you for your service.” I was down at NBC, having a conversation with Mike Barnicle and Willie Geist, and the subject of service came up. Willie’s father and Mike’s father had both served. Mike brought up the notion that people used to say, “What did you do in the service?” because everyone had served. We had something like 19 or 20 million people in uniform.

They didn’t say, “Thank you for your service,” because everybody had served. The question was, “What did you do in the service?” Since we’ve gone to an all-volunteer service, we’ve forgotten the notion of universal service. It’s more of a pity, but it’s interesting that you mentioned that after the day we had a similar discussion down at NBC.

That’s why I asked. You have done so much over the years. Besides your military service directly in the Vietnam War, you’ve done so many things since then that were in the service of your country. We appreciate it.

It’s my honor.

It’s very interesting you say that, Jack. Colonel Jacobs, if you don’t mind my calling you Jack.

Please do.

It’s very interesting. My father served in the Navy. In his later years, he was in one of the veterans’ homes in New Jersey. I would go to visit him, and 90% plus of the residents were military. His friends there would say to me, “Where did you serve?” It was an assumption that everybody was in the military. I said, “I didn’t. I was not in the military,” and they looked at me funny. This was a few years ago. These gentlemen and these women were all in their late 80s or early 90s at the time. You’re right. It was that mindset.

America’s Relationship with Civic Duty and Public Service

Jack, I read your book, which was fascinating to begin with. In your book, If Not Now, When?: Duty and Sacrifice in America’s Time of Need, there’s a theme that seems to be prevalent, which is America’s relationship with civic duty and public service. Were you trying to express that purposefully, or was that something that was underlying as a motif in the back of your mind?

It was the latter. Somebody once asked Hemingway, “How do you write?” He was among the most successful writers in American literary history. He said, “I don’t know. I just sat down and wrote. Most of what I wrote, I threw in the garbage.” He notoriously had big fights with his editors about what would be in the finished product. I’m not one of those people who sit down and say, “When I write, it’s going to follow this outline and so on.” It’s not an expository, in my case at least anyway. I just sit down, write, and edit later. What comes out, clearly, there’s a theme, but it’s not by design. It’s by happenstance.

What motivated you to write a book? Was it, “I want to put my thoughts down and see where it comes out?”

It’s an interesting story. I forget who it was who said that everybody has a book in them. A very good friend of mine named Ivan Kronenfeld, who had been a stevedore and an actor, is gone as a result of Parkinson’s disease. His widow is Anne Byrne, who was Dustin Hoffman’s first wife. They were married for a long time.

Ivan grabbed me. We had some mutual military friends. He wasn’t in the military, but most of his friends had been. We had a small group of people who got together. He grabbed me one time and said, “You need to write a book.” I said, “I don’t have any time for a book. It’s a pain in the neck. I don’t want to write a book.” He says, “You’re going to write one.”

He dragged me off to a publisher who said, “Give this guy a contract and make him write a book.” That’s the result of it. I had no intention of doing any writing. It’s in collaboration with a journeyman writer who let me put in whatever I wanted to put in, so it sounded just like me, who wrote this memoir. I had no intention of doing it in the first place, but I was satisfied with the result.

When you were writing the book, when in the course of writing the book did you say to yourself, “This is coming out okay. I like this. This is good for me.”

It was after the first 50 pages or so. I was an untested writer. They didn’t know if I could write or not. They weren’t going to give me any money to see whether or not I could write. They said, “We’re going to give you somebody who knows what he’s doing, Doug Century, to assist you.” Doug interviewed me, transcribed it, wrote out the first 50 pages or so, and sent it to me. I said, “This doesn’t sound like me. Here, let me show you what it should sound like.” It was after I had edited the transcription that I came to the conclusion that it was going to be okay, the first 50 pages, because it sounded like me. Even if there was nothing worthwhile in the manuscript, it at least sounded like I did.

How To Contribute to the Greater Good

In your book, you urge your readers to think critically about what it means to contribute to the greater good, whether you’re in uniform or not. I’d like you to embellish on that a bit. Hopefully, we have an audience. Our audience is primarily composed of business people. I’m not talking about Fortune 500 CEOs. I’m talking about Main Street executives who either own businesses or are executives within those businesses.

This is a different world now than it was for our parents because they all served. Every household had made a contribution to the defense of the Republic. As a result, everybody had been in service to the country by the time they were in their mid-20s and early 30s. Without thinking that you owed something to the country, you dove into making a living, raising a family, and so on.

Perhaps if you were successful when you got older and you had more time, you made further contributions to the Republic, but your service had already been accomplished by the time you were a relatively young adult. That doesn’t happen anymore because we’ve outsourced the defense of the Republic to a very small number of young men and women who are willing to do it. Most people have not made a contribution to their communities or the community at large by the time they’re middle-aged.

Let me ask you. Why do you think that’s the case? Is it because they’re not liking what they’re seeing, or don’t see the value in it?

A little bit of both. We have not inculcated in the succeeding generations the notion that if they live in a free country, they owe something in the form of service. We’ve made it easy for them not to do that. We’ve said, “We don’t need you to do anything for your country. We’re going to hire people and they’re going to do it for you.”

That is an extremely dangerous thing, particularly if you live in a democracy, to grow up with the idea that you don’t owe anybody anything. That’s not the way the world works. I don’t think we’re going to be satisfied with the result because of that notion, where we leave it up to somebody else, and then it’s going to work. That’ll work until it doesn’t work. When it doesn’t work, it’s going to fail catastrophically.

That’s both fascinating and terrifying at the same time. Let me ask you this question. If you had the only vote, how would you rectify it?

There should be a national service. You’re talking to somebody who believes in national service. There are ways to do it that are logistically and administratively not that difficult. At the end of the day, the independent variable is whether or not we have the political will to do it. We do not have the political will to do it.

Let me leave you with this notion. More people were killed in New York City on 9/11 than were killed at Pearl Harbor, a place very few people knew where it was in 1941. Hawaii did not become a state until I was in high school, and yet on the 8th of December 1941, hundreds of thousands of young people streamed to reception stations around the country and volunteered to go defend the Republic. We had 18 or 19 million people in uniform during the duration of the Second World War.

My father had been a student at the University of Minnesota, studying electrical engineering, and then, about eight weeks from graduation, got dragooned out of the school into the Army. He hated getting dragged out of school. He hated the Army. He fought in New Guinea and the Philippines with the Army. He hated getting shot at. Nobody likes that, and yet when he got to be my age, all he would talk about was how proud he was of having saved the world.

The day after 9/11, President George W. Bush said, “You don’t need to do anything. Go back to your homes. Go to a shopping center and spend some money.” When more people were killed on 9/11 than were killed at Pearl Harbor, there’s something wrong with how we think about what we owe the notion of the United States when you hear the President of the United States saying, “Don’t worry about it. It’s going to be taken care of.” It wasn’t taken care of. You could argue persuasively that we shouldn’t have done any of the things that we did after 9/11, but that’s all tactics and strategy. The idea of service and sacrifice has been lost among the population.

The idea of service and sacrifice has been lost among the population.

How War Impacted Our Sense of Civic Duty

Do you think that the Vietnam War impacted that feeling? To digress for a second, if anyone hasn’t been to Pearl Harbor and seen the memorial, you should go. It’s beautifully done and exceptionally well done. It is impactful when you go there. I’ve been there, and they’ve done a great job on what they created. In World War II, America was attacked, and people felt a sense of service after that point. Vietnam was a little bit different. Certainly, the way it ended didn’t go well. Do you think people were impacted by that war, and how that impacted their sense of civic duty?

Everything that happened both geopolitically, domestically, and politically after the Second World War had an impact on how we thought about and still think about our obligations to the defense of the country. Korea was the same way. We didn’t get attacked, but our interests were attacked. We have done a very poor job of rationalizing the difference between being physically attacked on the one hand and having our interests and/or those of our allies attacked. We don’t think clearly about the ramifications of what the relationships are in the geopolitical sphere anymore.

It’s interesting you mention Vietnam. That’s where I fought. At the end of the Second World War, there was Ho Chi Minh, whom we had advised during the Second World War. Don’t forget, we had advisors with Ho Chi Minh during the Second World War in our attempt and his attempt to get the Japanese out of Indochina. When the war was over, he asked us to assist him in getting the French out. We said, “We’re not going to do that because we’re part of NATO, and so is France,” forgetting for the moment that de Gaulle had taken the French Army out of NATO and did not have NATO’s interests at heart.

They only had de Gaulle’s interests at heart. Yet, we said, “We’re not going to do that because you’re a communist.” I’m not interested in supporting communists either, but we did not think clearly about the geopolitical variables involved in making the decision to go to Vietnam. Everything we did in Vietnam, everything we did in Korea, and everything we’ve done in the war since 9/11 has been on the cheap.

It has cost us a great deal of money and a great number of lives and treasure, but we’ve all done it by tying our hands behind our backs and saying, “We don’t have the political will to go all out and do what we need to do in order to win.” We’ve done a very poor job of articulating what winning means. I’m always amused by an observation by Lewis Carroll. We shouldn’t quote him. It’s not even his real name. In Through the Looking-Glass, I made an interesting observation. I forget which character said this, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.”

I use that expression all the time. I love it.

You’re supposed to start at the end and work backwards. In the military, you can’t tell the lowest-ranking, dumbest private, no-class dogface to do anything unless you first articulate what the objective is. Yet, in our daily lives, in our own businesses, in our personal lives, in the use of the military, in economic and diplomatic instruments of policy, we don’t do that. We hardly do that. To the extent that we don’t do that, we have an excellent chance of failing.

We didn’t do that in Vietnam. We didn’t say, “This is what we wanted to look like. These are the steps we’ve tested empirically to indicate that this is what we need to do in order to achieve these objectives.” We didn’t do that at all. We incrementalized everything. We sent a few thousand people to Vietnam, and then we sent a few tens of thousands of people to Vietnam, and then we sent a few hundreds of thousands of people to Vietnam.

When I got to Vietnam, there were half a million Americans in Vietnam. We were conducting exactly the same tactical operations at the end of my tour as we had at the beginning of the tour. We just called it something different. Yet, we still didn’t achieve our objectives because we never said what they were. The same thing was true in Iraq, Afghanistan, and so on. We’re lousy at saying what it is we want to accomplish.

You’re right. I know when I was a child in elementary school, we talked about the spread of communism. It was like, “This is the first step to block the spread of communism.” That’s why you had SEATO besides NATO, supposedly, at the time. Do you think that if our politicians or the president at the time did that, people would be receptive to that, or they would’ve said, “No way. We’re not doing that. It’s over there, not here.”

Don’t forget. There are lots of actors here. They’re not just the guys on the other side of the Atlantic and Pacific whom we’re trying to influence. There’s also a constituency in the United States. It’s not only the electorate. You’ve got 535 people who think that they know everything and who also have something to say. Don’t forget that under normal circumstances, it’s Congress that decides how we’re going to pay for any of this. Nothing is for free.

We don’t coordinate our activities very well. I’ll give you a good example. When it means the most, we do not have an industrial policy. We certainly don’t have a military-industrial policy. We’re supposed to be building two Columbia-class submarines a year. We’re building fewer than one a year. One of the reasons is that the military-industrial base doesn’t exist. We don’t have the capability, no matter how much money has been appropriated, to accomplish specific goals like buying 155 millimeter artillery shells or submarines. We don’t have the industrial base to accomplish it the way we need to accomplish it.

Contrast that with what happened during the Second World War. During the Second World War, we had a public-private partnership. Necessity is the mother of invention. We had a public-private partnership in which we used to outproduce the entire Axis. They lost, not solely because of that, but that in conjunction with the valor and fidelity of the people in uniform and our allies. We couldn’t have done it without this public-private partnership that existed in the form of the military-industrial base. We would knock their socks off.

Anyone who follows that knows exactly that was the case at the time. America became a monster in the industrial establishment.

Are you suggesting that at this point, the United States is compromised by virtue of the fact that we’re effectively outsourcing or have outsourced all of our manufacturing capabilities?

Yes. That’s one of the reasons why we’re being outclassed. Not that we’ve outsourced our capabilities, but we don’t have capabilities because we have not structured the acquisition of the things we need in order to fight and sustain our military apparatus. We have not structured it in such a way that it’s not fragmented. When you take a look at the budget, they have line items there, and they’re not necessarily interrelated in any fashion.

There’s no coordination or very little. You should never say never or always, and you shouldn’t say all or none. There’s insufficient coordination between the government, on the one hand, which includes all three branches of government, and the private sector, on the other, to achieve the national security objectives we set for ourselves. There’s no coordination. Without coordination, I’m afraid you’re not going to achieve what you need to achieve. We’re not doing it.

Shaping Better Military and Civilian Leaders

If that’s the case, which qualities do you believe are most lacking in today’s leaders, both military and civilian?

Leadership writ large.

How can you change that? Is it one of those things where a psychiatrist says that’s the one to change by itself? Is it a matter of the right people stepping up or the public recognizing that we have the wrong people in the wrong places?

Both of those. They’re not mutually exclusive. This sounds terribly elitist, so maybe you want to cut it out. There was a person who was not a particularly nice human being who, for many years, was a very good writer. He wrote for the New Yorker. He once wrote, “Nobody ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the American public.” You could argue strenuously that he didn’t know what he was talking about.

I would argue that some of the results that we see in the political sphere, which have a direct result on what we see in the geopolitical sphere, are a result of what H. L. Mencken wrote. The public has got to be much better informed than it is now. Why isn’t it? There are a lot of distractions. The quality of education starting at the very beginning of people’s education, by and large, is lousy. People don’t have a sense of history because they’re never taught to have a sense of history. Nobody pays very much attention to things. We outsource everything. As long as we’re on the receiving end, we’re happy as long as we’re getting what we want.

Nobody feels any obligation to do what they need to do to make a contribution to all the things we’ve mentioned, education, politics, and so on. We demand very little of our elected leaders. As long as we agree with them, that’s okay, but that’s not how politics either used to work or is supposed to work. I’m afraid we’re our own worst enemies. Leadership is certainly something that can be taught. The time to teach it starts at home when you’re two years old and needs to continue through grammar school and higher education. We don’t do a good job of that at all.

Are you suggesting that at this point, the country is effectively in crisis, devoid of leadership? It’s not a leading question. I’m just trying to engage in the conversation.

It’s not devoid of leadership, but I think the leadership leaves a lot to be desired. Our leaders are people whom we decide we agree with.

The Importance of Verifying Information

To your point about information, that’s one of the problems. We hear from everyone that you don’t know what information to trust. Where do you get it? Is it opinion, or is it information? Are they facts? Are they alternative facts? You’re on television. You’re on the streaming news. The young people talk about the fact, “I can’t believe anything I listen to.”

How do you get that point across? How do you convince people whether it’s additional information or whether they should be informed? When you’re on television, how do you convey, “What I’m telling you is the truth,” or “These are facts,” when everybody is so negative or so questionable about these things? You hear that all the time.

You have to preface everything you say by saying, “Let me tell you this. This is true,” without coloring it. There used to be an obligation on the part of the broadcasters to produce real news and facts, which had been empirically verified by more than one independent source. I remember lots of times when I first got involved in being on TV that I couldn’t and didn’t want to say anything unless it had been verified independently by two separate sources. That’s not the case anymore, is it? More is the pity.

What has happened is that technology has something to do with it. Don’t forget that you can’t get a broadcast license unless you broadcast news like we were talking about. The FCC would not renew your license to broadcast unless you were even-handed about everything that you said on the air. The Federal government controlled the broadcast spectrum. That doesn’t exist anymore. The FCC doesn’t have any influence over anything other than the broadcast spectrum. They don’t have any influence over podcasts, schmodcasts, and any of that other stuff. They have no influence over that. As a result, anything that you say that’s not on a broadcast, you can say with impunity, present it as a fact, when in fact, it’s not a fact.

It’s harder when someone comes on television for the White House and says, “These are alternative facts. Those are your facts. We have alternative facts.” It’s tough to digest that and say, “What’s what here? What do I believe?”

Why do people swallow that? They swallow it because they were never taught otherwise. There are lots of ways to fix systems. One way to fix a system, and there’s going to be a lag, and it’s going to take a long time to fix this, is you have to fix it at the very beginning. If people go to school and learn that anything anybody says is accurate, whether we can prove it or not, then you’re going to have an entire generation growing up to believe anything that they are told. You’ve got to start at the beginning. How do we want people to think? If we don’t care how they think, then they’re going to continue to be taught exactly the way they’re taught now.

The Importance of Verifying Information

You’ve been a leader your whole life, whether in the military, in your business career, in writing your book, and so on and so forth. What qualities, from your perspective, distinguish a good leader?

There are lots of qualities, but adherence to the truth is probably the most important one. You can’t say anything, and you shouldn’t say anything that you know inherently not to be true. You have to be able to distinguish between your opinion on the one hand and the facts, as they can be empirically presented on the other.

I remember when I went to school, that’s exactly how information was delivered to me. “These are the facts. Let me tell you what I think about this,” said my teachers, my professors, and so on. You grew up with the notion that there’s a difference between fact and opinion. Leadership requires people at the grassroots to change how they do things, but that’s not the case.

We don’t have a national way of controlling education. All education is local. All taxes are local. Tip O’Neill said, “All politics are local. Everything is local.” Everything has got to happen at the local level. If leaders at the local level stink, then everything at the higher levels is going to stink, too. We have to grab control of whatever we can, probably at the local level, in our homes and in our communities, if we’re ever going to get leaders at the national level who will be able to respond to what this country needs and to be good leaders.

All politics are local. If leaders at the local level stink, everything at the higher levels will stink too.

When you watch leaders now, the philosophy for many is, “If I say it often enough and loud enough, people are going to think it’s true.” How do you change that mindset to the lower level to say, “You can’t act like that. You can’t behave like that. That’s wrong. Simply saying something doesn’t make it true,” but that seems to be the position now. It makes it hard for people to argue back and say, “Simply because you do that doesn’t make it right.”

You described real heroism. You’ve got to be able to stand up. It’s easy to get on television and say, “This stinks.” If nobody agrees with you or they hate you, what are they going to do? It takes real courage to stand up in your community and tell somebody who is spewing rot that he’s spewing rot when the people are right there and you’re among your neighbors. How can you do it? It takes courage to do that. We have to find some way to develop courage at the lowest possible level.

When you fight a war, there is courage every single day in every single engagement. Somebody once asked me, “What did you think about the protests back home when you were fighting in Vietnam?” My response was, and still is, “When people are ardently trying to kill you and you know that your objective is to eliminate the bad guys and save the good guys, you’re not thinking about any of the nonsense. You’re not thinking about any of that stuff. You’re thinking only about killing the bad guys and taking care of the good guys.”

That was the philosophy behind The Band of Brothers.

We need to think the same way about you’re not going to be able to fix things nationally unless and until we have the courage to fix things locally. You’re not going to get somebody who’s going to rise to the top of the food chain at the state or national level unless and until we can nurture them to maturity at the local level. That takes real courage because you’ve got to stand up among your fellows in the community and tell somebody who’s full of baloney that he’s full of baloney.

Revenue Generation vs. Culture Building

Let’s change gears for a moment, using that as the theme. Let’s talk about business leaders now. Generally speaking, it seems to me as though most business leaders are talking about culture and not practicing culture. They’re practicing revenue and revenue generation. If you had your druthers, what would you say to business leaders now about the difference between revenue generation and creating a proper culture in your business?

They’re not necessarily mutually exclusive, but a part of the problem occurs when a business leader says, “These are different things. Furthermore, not only are they different, but they’re mutually exclusive.” That is to say if we’re working hard to achieve a very healthy bottom line, we are, a priori, going to have a crappy culture. That’s not true at all. I’ve been in lots of organizations that have managed to do both. It takes leadership in order to do that. It does take the ability to convince the people who are in the organization that these two things are not mutually exclusive.

How do you sell it to shareholders in a publicly traded company, which is where Stuart is going with this, a little bit?

If you start with the notion that a healthy company is more likely to produce satisfactory or even exceptional bottom-line results than an unhealthy one, especially if the results prove it, you can convince shareholders that you’re in good shape. In many organizations that I’ve seen, if the focus is solely on the achievement of a spectacular bottom line, that doesn’t last very long.

If the focus of an organization is solely on the achievement of a spectacular bottom line, that does not last very long.

I’ll give you some good examples, or I’ll give you a class of good examples. Back before 2008, you could make a great deal of money in a wide variety of ways, many of which you can’t make now because we’ve become automated. There were big gaps and anomalies in the marketplace that you could drive a truck through. Financial organizations in particular, but investment organizations generally writ large, would take a look at what they were doing with some trading style or some business style and say, “We’re doing this with about two times leverage. If we only did this with 10 times leverage, we’d make 5 times more. If we did it with 20 times leverage, we’d make 10 times more.”

They were not recognizing that the risk-adjusted return on capital was not only lousy, but it was debilitating. In an absolute sense, over a short period of time, they were making a great deal of money, so they went ahead and did it. If they took a look at their own ray rock parameters that were established for very good reason, they would see that they’re not supposed to do that. You may make some money for about 6 months, 1 year, or 2 years, but you’re going to blow yourself up. They did it anyway.

These were some very big names, people who you would think were led by smart guys and therefore ought to know what they’re doing, but they didn’t know what they were doing. Their culture coincided with the vast reduction and the risk-adjusted return on capital. They were mutually reinforcing. You had lousy leadership doing greedy things inside an organization with a crappy culture. What was the result? The result was a lousy return. It was bankruptcy. A healthy corporate culture and good returns are not mutually exclusive. They’re mutually reinforcing, especially with good leadership.

Fighting in the Vietnam War

Jack, can I switch gears for a minute? I have to ask you this question because, in reading your bio and reading your book, when you went to Rutgers, and I’m a proud alumnus of Rutgers as well, you signed up for the ROTC. It was right in the middle of the war. It was starting to ramp up. You had to know at the time that you were going to end up over in Vietnam.

What was your mindset at the time, knowing that was the case? Certainly, it wasn’t a popular war. People were still learning about it as well. How did you feel? Give me your state of mind because it’s certainly interesting to me when you know that was going to be the case. It wasn’t World War II. When we were attacked, it wasn’t the same perception. What was your state of mind at the time?

I started at Rutgers as a freshman in 1962. That was before we sent troops to Vietnam with any consequence. We didn’t send large-scale numbers of troops to Vietnam until ‘65, which was the year before I graduated. It wasn’t until I was a junior in college that it was clear that if and when I was commissioned and went into the Army, I’d wind up in Vietnam.

There were two independent variables here that focused my attention. One was that when you became a junior in ROTC, you made a commitment to go into uniform. They paid you $27 a month, which wasn’t even a lot of money back in those days, but $27 is $27. I got married when I was eighteen years old, so I had a wife, a daughter, and so on. $27 meant something, even though it wasn’t a great deal of money.

The most important factor was the fact that my father had served in the Second World War. I thought it was my obligation to serve. Going to Vietnam, going to Timbuktu, and going to any place was not relevant. What was relevant was that I had an obligation to serve my country. My objective was to do my three years, which was my obligation after getting commissioned, and then get out. I was going to get out and do something else, like become a lawyer.

How did that work out for you?

That’s a very good point. Do you know why I stayed? I stayed because I loved the people. I didn’t want to leave them. My obligation was through. I didn’t have to stay in, but I loved the people, and I didn’t want to leave them. When people ask me what I miss most about the Army, it’s the people. I always feel better when I’m around people who are either serving or have served. The fact that I was going to go to Vietnam and maybe wind up a casualty, it’s not that it didn’t cross my mind. It was far secondary to the imperative of having to serve. I thought it was my obligation to serve.

In the context of serving, Stuart brought up the issue of leadership in this world. The value of being in the military, how was that impactful on your sense of leadership and the leadership skills you developed over time?

I talk all the time to kids who are leaving the service. I said, “I was a machine gunner. I was a squad leader in the Army. What do I have to offer?” The fact of the matter is that nobody gets more authority and responsibility at an early age than somebody in uniform. You’ve got 19-year-old or 20-year-old kids who are responsible for a quadrillion dollars worth of equipment and the lives of 40 people.

I did a package for NBC Nightly News one time aboard the George H. W. Bush. My pitch was, “You got 19-year-old kids responsible for $2 billion worth of equipment.” I made sure everybody I interviewed was below the grade of E-5. That’s a sergeant or a petty officer. These kids are responsible for an enormous number of people.

My father was a sergeant in the Army during the Second World War. Don’t forget, he was a sergeant. His troops call him the old man. Do you know why? He was 26, and they were all 18 and 19. As far as they were concerned, he was ancient. This is a long-winded way of saying when I got out of the Army, I went into the banking business. I went into the fixed income business. I had never taken an economics course in my life.

The first day I showed up for work, I didn’t know that there was an inverse relationship between the price and the yield of a bond. I didn’t know anything, but I’ve been in charge of 1,000 people. Nobody was shooting at me. I was like, “How hard could this be?” It wasn’t hard. Once you’ve been in uniform, you can do anything. You need two minutes to figure it out, and you’ll figure it out. It’s military service that gives people everything they need to learn something new and be successful.

Don’t forget that when the war ended in 1945, that whole generation of people presided over the biggest increase in the standard of living in this country in its history. One of the reasons was that they may have been 25 or 26 years old, but they’d seen a lifetime of leadership experience they’d participated in, and they could do anything. We have to not forget that all these kids in uniform can do anything. That’s what influenced me. That’s what made me successful.

The military builds a can-do attitude no matter what you’re faced with.

Resolving the Conflicts in Ukraine and Middle East

We only have a few minutes left. I want to ask your opinion on two things. Number one, how do you believe the war in Ukraine is going to resolve? Number two, the conflict in the Middle East.

Ukraine is interesting. I am reminded of an observation by Henry Kissinger when the war in Ukraine first started. He said, “This will end with a negotiation.” He was the king of negotiation in any case. He said, “Probably, what’s going to happen is the following. Russia will agree to leave any terrain they have acquired except for Crimea and Donbas, and they’ll give up their aspiration to have a land bridge to Moldova and control of all of the Black Sea Coast.” That’s probably how it’s going to end. Ukraine will agree to get rid of the majority of Russian forces from its terrain. It sure smells like that’s how it’s going to end.

Do you think NATO is a non-issue, then, for Ukraine?

Yeah, at least for the moment. Part of the negotiation is probably going to be that Ukraine can’t be part of NATO for 5 years or 10 years or something like that. You know the old Wall Street saying. You don’t get what you deserve. You get what you negotiate. What Ukraine deserves is to have Russia annihilated. That’s what we all deserve, but that’s not what’s going to happen.

Russia hasn’t changed in many years. It’s the same as it’s been since Ivan the Terrible, and it’s not going to change anytime soon. It’s a question of negotiation. If you were a betting man, you’d probably think that what Kissinger said is correct. It’s not going to be what’s the most likely event. I forget who it was who said, “The race might not be to the swiftest, but that’s how you’re supposed to bet.”

Good point. The second part of Stuart’s question regarding the Middle East, your thoughts?

I’ve been wrong about this. I would’ve thought that, because of the tremendous labor intensity, capital intensity, and time intensity of occupying Gaza that Israel would want to bail. They’ve been in Gaza before and didn’t like it very much. You have to call up 100,000 reservists, which economically is tough to do, to be on constant watch down in Gaza. That’s a very expensive thing to do.

I would’ve thought that Israel would be disinclined to do that, to occupy Gaza, because it’s an expensive thing to do. Yet, it would appear that that’s what they’re working on. I don’t know the long-term military and economic implications of occupying Gaza, but they’re probably not attractive, especially in this economic environment. If interest rates were zero, maybe it would be more conducive for them to do so. Under the circumstances, it’s extremely difficult geopolitically to project ahead and say, “Five years from now, we’re going to control Gaza.” That’s going to be a very expensive thing to do.

On the other hand, don’t forget that there’s a domestic political component to this. Netanyahu has a lot of people to answer for. That may be one of the independent variables that’s driving all this. It’s hard to envision how Israel is going to be able to control all of that five years from now. You’ve got millions of Gazans there.

Do you think they want to control it, or do they cease control as long as they get Hamas out?

I think the latter, but how do you get Hamas out without taking over and controlling it? It’s not like you can rely on the PLO to do this for you. Nobody believes the PLO can do anything. Everybody hates the PLO, including the rank and file.

They’ve shown they’re inept. They’re corrupt, and they’re inept.

They can’t do it, so who’s going to run it? The only person who has demonstrated that they can run it is Hamas. Nobody wants Hamas to do that, including the Gazans. Israel is the default. It is going to be a very expensive proposition.

You don’t think that Trump and the Kushners are going to come in there and create something?

The National Commanding Authority is going to continue to support Israel. There’s no doubt about that. No matter how much money is given to Israel, that’s beside the point. It is labor-intensive. You’ve got to have actual human beings there. For every reservist who’s walking a patrol in Gaza, that’s one fewer person who’s making a contribution to the gross domestic product of Israel.

It’s not a question of money per se. It’s a question of manpower. Israel needs all these smart people who are reservists to be doing things in economic entities inside Israel to write code, develop new drugs, and do all the things that Israel does well. Walking a beat in Gaza may be satisfactory from a national security standpoint, but for a long-term economic standpoint, it’s going to be troublesome.

How the U.S. Can Treat Veterans Better

That’s not a good use of human capital. I have one quick question before Stuart asks our final question, because this is central to all of us. What is your perspective on how the United States doesn’t honor its veterans or treat its veterans?

It does a much better job than it used to. I remember when I first got out of the Army, I went down to the local VA hospital and I had to get an appointment to get an appointment. That’s not true anymore. A variety of people have made it much better now than it was before. Guys like Bob McDonald, for example, who was a student of mine at West Point when he was a cadet, grew up to be chairman of Procter & Gamble and eventually became the Head of the Department of Veterans Affairs. He was one of the many people who made the VA a good organization in many respects. If you’re a veteran and you walk into the VA, and you need your eyeballs recalibrated, they’ll recalibrate your eyeballs in about ten seconds. They’re good now. We do that well.

We don’t have a good handle on what people who have served in uniform are doing for the Republic because none of us does. It’s easy to say, “Thank you for your service,” because we don’t have to serve. That’s an easy way to do it. We don’t have a good view of what people who have been veterans have done, but at the end of the day, we don’t have to. What else are we going to do? We have Veterans Day, where we tell veterans, “Thank you for your service.”

I don’t think we need to do much more. What we need to do is all make a contribution to the Republic’s defense. Once we do that, all of these problems about, “What are we going to do about veterans? They do so much for us,” will be solved. It’s a psyche that we’ve lost, and we have to regain it. We’re doing as much as we possibly can at the moment. We keep doing what we’re doing. The defense of the country is very difficult to do when you’ve only got less than one-half or 1% on active duty who are doing it. That’s not satisfactory.

Military Lessons for Young Business Owners

Jack, let me ask you one parting question here, and then Norman has our survey question for this episode. What advice would you give a young business owner, whether she or he has come out of the military or otherwise?

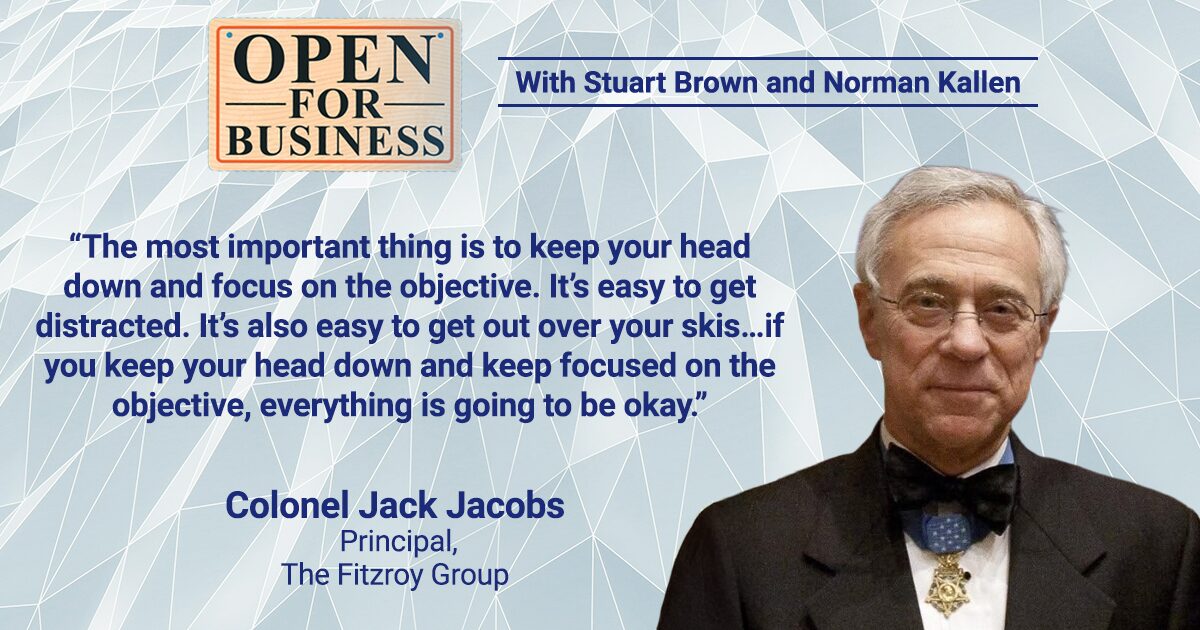

It depends on what the business is. The most important thing is to keep your head down and focus on the objective. It’s easy to get distracted. It’s also easy to get out over your skis. It’s like, “We’re successful, so let’s borrow some more money. Let’s use more leverage. Let’s overstock.” Don’t be enticed by any of that stuff. If you keep your head down and keep focused on the objective, everything is going to be okay. It’s very difficult to be a small business owner and become a multi-billionaire within five years.

If you keep your head down and keep focused on the objective, everything will be okay.

When you went out and talked to people about funding a business, if they wanted to see 5-year proformas, they would see 5-year proformas. It’s like, “I’ll give you five-year proformas.” Anything longer in duration than eighteen months is baloney. It’s all made up. If you show up with eighteen-month proformas, they throw you out there, and they want to talk to you.

They’re like, “What are you talking about?” You’re like, “Hold on a second. Let me get my eraser. In your presence, I’ll do another three and a half years for you. How does that look? Does that look good? We got this hockey stick. It goes to $18 trillion within 5 years.” You’ve got to be realistic, focus on realistic objectives, and work towards that. Don’t make it up. The siren call of hockey stick increase is all baloney. Don’t start believing your own press releases. Once you do that, you’re dead.

I have one last question on the lighter side before we go. First of all, I have to ask you. Do you drink alcohol?

I do.

Good. I needed some positive background for this. Are you a bourbon or a scotch drinker, and why or why not? What do you prefer, and why?

I prefer scotch to bourbon. I find bourbon too sweet and cloying, and I find scotch, even very heavily peated scotch, much more sophisticated. It’s not that it’s going to make me sophisticated. Nothing is going to do that. It’s more to my palate than bourbon.

Do you like it on the rocks? Do you like it neat? How do you like it?

Neat. First of all, life is too short to drink bad anything, whether it is bad wine, bad bourbon, or bad scotch. When I do drink scotch, I drink good scotch, and I drink it neat sometimes with a tiny bit of water.

Jack, this has been an absolute pleasure. First of all, it’s good to see you again. You look wonderful. This has been tremendously informative. I enjoyed the conversation. Thank you.

I did, too. Anytime you want me back, you are welcome to it.

Jack, thanks again. We appreciate it.

Important Links

- Colonel Jack Jacobs

- If Not Now, When?: Duty and Sacrifice in America’s Time of Need

- Through the Looking-Glass

About Colonel Jack Jacobs

Through the ROTC program, Jack Jacobs joined the American Army as a Second Lieutenant. He was an executive officer of an infantry battalion in the 7th Infantry Division, a platoon leader in the 82nd Airborne Division and the commander of the 4th Battalion 10th Infantry in Panama. Jacobs was a professor at the US Military Academy where he taught comparative politics and international affairs. He was also a professor at the National War College in Washington, DC. He served as an advisor to Vietnamese infantry battalions during both of his deployments to Vietnam, earning three Bronze Stars, two Silver Stars and the Medal of Honor, the country’s highest combat honor. In 1987, Jacobs took his Colonel retirement.

He was the founder and COO of AutoFinance Group Inc., which was one of the companies that invented the securitization of loan instruments. He managed foreign exchange options globally as a Managing Director for Bankers Trust and was a partner in the institutional hedge fund industry. Jacobs later established a comparable company for Lehman Brothers before returning to retirement to explore investing. He serves as a principal for The Fitzroy Group, a company that invests both on its own account and in joint ventures with other institutions and focuses on the development of residential real estate in London. He is a Director Emeritus of the World War II Museum and serves on the boards of several charity organizations.

Subscribe Today!