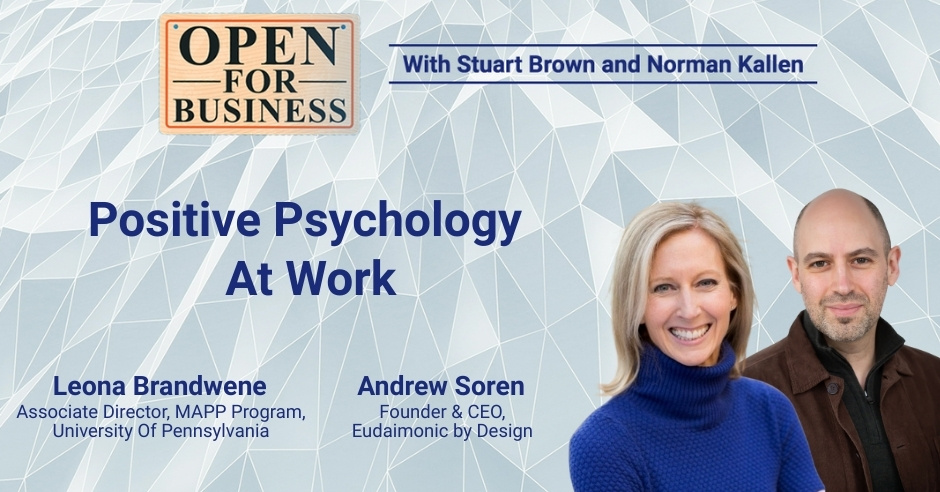

Positive Psychology at Work with Leona Brandwene and Andrew Soren

Every workplace must prioritize everyone’s happiness to produce the right results and retain the right people. With the proper grasp of positive psychology, business leaders can elevate their cultures and help the entire team flourish. Exploring this topic with Norman Kallen and Stuart Brown with Leona Brandwene of the University of Pennsylvania and Andrew Soren of Eudaimonic by Design.They discuss how positive psychology can lead to a resilient business, empower employee management, and help address work-related stress. Leona and Andrew also share how they take care of their own well-being and the importance of surrounding yourself with positive individuals.

—

Positive Psychology at Work with Leona Brandwene and Andrew Soren

I’m interested in our guests. I’m saying guests because it’s plural. We’re going to be joined by someone who lives at the intersection of science and the human soul.

That’s pretty deep, Stuart.

It is. Who are we meeting with, Norman?

We’re meeting with a woman by the name of Leona Brandwene. She is the Associate Director of Education at the University of Pennsylvania’s Positive Psychology Center. She has played a vital role in shaping the next generation of positive psychology practitioners through the Master’s of Applied Positive Psychology, MAPP program, and beyond.

She was, from what I’m told, one of the first graduates of the program back in 2010. The Center for Applied Positive Psychology was established at UPenn by the renowned professor Dr. Martin Seligman in 2003. I don’t want to date myself, but I’m a Penn grad. I took a course with Dr. Seligman, as did my wife, back in the ‘80s. I credit my wife for this episode because Dr. Seligman was a huge and profound influence on my wife. She has always wanted, in effect, to study happiness. This program began and was derived from the study of happiness. We’re going to learn more about that when Leona joins us.

It’s a great discussion because too often, for business owners, their attitude is, “This is work. We’ve got things to get done.” Once you understand what she’s going to talk about and you talk to people who are in this area, you finally learn to appreciate that when you have employees or employers who understand the concept of happiness, and how that adds to productivity and worker engagement, it’s meaningful.

To not keep our readers on the edge of their seats for too long, we do have a second guest joining us during this episode. His name is Andrew Soren. Andrew is a leadership coach, an organizational consultant, and is also the Founder and CEO of a company by the name of Eudaimonic by Design, which is a global consultancy dedicated to helping organizations design cultures where people thrive and, hopefully, are happy. He’s also a graduate of Penn’s MAPP program, which is the same program where he remains an active contributor to the alumni network and the learning community there. We look forward to Andrew joining us.

With that background in mind, which spans national healthcare consulting, academic leadership, and on-the-ground coaching, we’d like to welcome Leona to our program and get more information and background on what it is that she does, with respect to business owners, people, and academia as a whole.

Here we are. Welcome, Leona. Welcome, Andrew, to Open For Business.

Thank you for having us here.

It’s a pleasure. We are thrilled to have you guys here. People may be wondering on the show why we want college professors and professionals in positive psychology. Let me explain when this all began. Several years ago, back in the 1980s, my wife and I were both happy to be Penn students at the time. We took classes with Dr. Martin Seligman, who is, from what I understand, the founder of this program.

From that time that we took those courses forward, more so my wife than I have to admit, she has been enamored with the concept of studying happiness. We were talking about it at dinner a few months ago. I said that it may be very interesting if we can find the right people at Penn who could speak on this subject. Welcome to the show. Remember, there’s no pressure on you, notwithstanding the fact that this has been developing since the 1980s.

Thank you for sharing that story.

Understanding Positive Psychology

It’s a great story. It’s wonderful how you connect and what you remember. By way of background, how did you get involved in this positive psychology? Certainly, I can’t imagine that all of a sudden, one day, you woke up, the light went off, and you said, “I need to get involved in positive psychology. That’s what I want to do for a living.” Give us, if you wouldn’t mind, both your backgrounds, why you got involved in this, and what attracted you to it.

Stuart, my background is not too dissimilar to your wife’s experience, except I did not take undergraduate classes with Martin. My pathway to it came through healthcare. I had been working on some national projects related to intensive care units, which are where they see the sickest of the sick in hospitals. We were working on a number of different disease states. Our approach to it was that we would bring together multidisciplinary professionals in these contexts and begin to work with them by setting goals and working on a vision towards addressing some of these key disease states that were important to clinicians in that setting.

One artifact of that experience, aside from what we were able to accomplish with those disease states, was that in healthcare, often, we see a lot of burnout amongst professionals. We see professionals who quickly become very unhappy. There’s a lot of intrusion into their personal lives. It’s exhausting. Often, the response to professionals who are in that situation is, “Go take a bubble bath. You need to relax a little bit, and that’s going to remediate everything.”

People often think about positive psychology as the science of happiness. It is actually the science of flourishing.

In particular, I remember there was this one organization that had turnover that was close to 50%, which is an extraordinary number in an intensive care unit. We started working with that particular organization. We didn’t do anything to address the turnover specifically, but what we did was we worked on building teams and helping them to work together toward a goal, and how they were interacting with one another in a professional and collegial manner.

In doing that, within about two years’ time, they went from having 50% turnover to having very low turnover, and a waiting list of people who wanted to get in and work in that ICU. It made me curious about how that happened when we didn’t do anything to speak about burnout, but what it was was that we were increasing the well-being of the professionals in that setting. That made me curious. That started me on my own exploratory adventure. That was how I discovered positive psychology and Martin Seligman’s program, the Master of Applied Positive Psychology at Penn.

Can you both describe what positive psychology is for our readers who don’t understand it?

Often, people think about it as the science of happiness. I’d encourage you to think of it instead as the science of flourishing. We use a botanical metaphor for a reason. Think about a flower in a garden. When you think about happiness, you think about sunny days, the sun always shining, and the flowers turning toward the sun.

That’s very important, but flourishing for a flower is more than that. It’s the ability to withstand the elements and the ability to develop a strong root structure. Fertilizer is necessary. Rainy days are necessary, too. The ability of that plant to be able to flourish in that context is reliant not only on a lot of conditions, but its response to those conditions to strengthen itself.

Positive psychology and the science of flourishing are quite similar in that fashion. It is about how people bring together a number of elements in their lives that help them not only to flourish, but to grow and strengthen themselves, so that when hard times come, because we are all subject to the vicissitudes of life at some point or another, we have the skills, the coping, and the capabilities to withstand some of those hard times. We can weather those storms and come out of them on the other side, potentially even stronger for the experience.

Surrounding Yourself with Positive People

Before we talk about businesses, on a more personal level, I’ve read that to be positive, one of the most important things is to surround yourself with positive people. It makes a difference. I read a simple book called Be the Sun, Not the Salt. You don’t want to jettison friends, but sometimes, we all have friends who are downers. It’s like, “The sky is always gray. The shade is always down.” From a more personal level, before we get into these other topics, how do you address those types of things? What do you do about that? What would you recommend or suggest?

There has been so much research. This field of positive psychology, which emerged as a thing called positive psychology, started in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. Since then, there has been an exponential amount of research. Every year, the amount of research that has been done almost doubles within this field. It’s one of the fastest-growing fields within psychology in terms of the quantity of research that is created.

Those people who look across the board at what are the most important factors of our well-being and our happiness, they would say it’s other people. One of the founders of the field of positive psychology, his name was Chris Peterson. He used to say, “If you looked at all of the research about what makes us happy and you wanted to boil it down to one central finding, it would be that other people matter.”

Other people matter to our well-being. It’s so critical when you think about the ideas of social support. When you think about the ideas of all the things that give us a sense of meaning, that bring momentary and lasting happiness into our lives, and that allow us to achieve things, we don’t do it alone. Some people are hell in our world, but for the vast majority, we need other people. Other people are contagious. Other people’s happiness is contagious. Other people’s misery is contagious. The way that we think about that collectively is an important thing.

Introducing Leona Brandwene and Andrew Soren

First of all, let’s do this. Andrew, can you please introduce yourself?

My name is Andrew Soren. Amongst many other things, I have been involved in the Master’s of Applied Positive Psychology program at the University of Pennsylvania for about 12 or 13 years since I was a student myself in that program, and have been part of the instructional team ever since. The thing that I mostly do is run a business that is about applying positive psychology in an organizational context.

Similar to Leona, my story of discovering this world was from working in the industry. I used to work in a bank. I spent about fifteen years working in a big bank in Canada. One of the major things that I had accountability for was leadership strategy and culture within the organization. That role was largely within a human resources or human capital context.

My experience of those roles was that we spent a lot more time thinking about the resource or the capital than we did the human. I was always interested in what it takes for people to perform in a way that was at their very best and what that would look like. We were an organization that spent a lot of time talking about high-performance culture, but we would talk about that in the context of productivity ratios.

We rarely talked about that from a place of, “What does it mean for someone to be their full potential in an organization? What does a tremendous amount of engagement look like? What does discretionary performance mean? How do we get people to want to show up, to find meaning in their work, to feel so engaged and absorbed in what they’re doing that they lose track of time and they’re like, “How did it fly by already?”

That was the kind of thing that I wanted to explore. In my exploration and research, the field that studied that was the field of positive psychology. It was the reason why I wanted to go to Penn. It was the reason why I wanted to study specifically with Seligman in the work that Penn was doing around, trying to understand what these ingredients are, as Leona was talking about, to help people not just survive, but thrive and flourish. That’s what I’ve been doing for the last few years.

Differences Between Happiness and Well-Being

Leona, what does happiness mean? How is somebody happy?

Let’s differentiate happiness from well-being.

How we function well in life matters. How we respond to our emotions might feel less savory, but they are not less important in the entire human life experience.

I’m glad you asked Leona this question.

Let’s be frank. When we look at it from an academic perspective, we’re trying to come to some consensual definitions so that we’re all pretty much talking about the same thing when we have some of these conversations. I’m going to pick on the name of Andrew’s business, which is called Eudaimonic by Design. Eudaimonic is a Greek word. I’m going to pair that with another Greek word that is called hedonic.

I’m going to oversimplify this wildly. There are two different aspects when we look across all the models of well-being and happiness that are out there that tend to bubble up to the top. There are things that fall under the hedonic side of well-being, which is feeling good. That tends to be the happiness side of well-being. There’s the Eudaimonic side of well-being, which is how you’re functioning well and having a fulfilling life.

Daniel Kahneman would’ve distilled it down into pleasure and purpose as being the two essential elements that go along with well-being. When we think about happiness, so often, happiness is associated with that hedonic side or the pleasure side, which is the feeling of feeling happy, feeling upbeat, or feeling as though things are going well in your life.

We have an entire spectrum of human emotions that we’ve evolved to experience for very good reasons, because all of those emotions have a functional and contributive aspect to our ability to be adaptive and to thrive in life. On the Eudaimonic side, how we function well in life matters. That particularly means how we can respond to some of the emotions that might feel a little less savory but are no less important in the experience over the course of an entire human life.

Happiness is the feeling side, but then we have all these other aspects, which include that sense of engagement at work that Andrew was talking about, whether or not we are able to sense-make about what our lives are about. If work is just an endless pile of tasks that feels meaningless, boring, and soul-sucking versus if we look at our work as having this arc of purpose that goes along with it where we say, “This is why I do what I do, because on this greater level, I’m contributing to the greater good with what I do.” That’s a powerful motivator at work.

Isn’t that generational? When you think of the Baby Boomers, it was, “Put your nose to the grindstone and work.” The Gen Zs and the Millennials are like, “I have to have meaning to work. I have to feel good about it. I have to have a purpose.” I’m not quite sure what the right and wrong answer is there, but I thought of that as you were saying that because, to me, it’s so generational in what your perspective is on what work is.

That’s such a great point. One point I want to make overall, when we talk about generational differences, is that there certainly are differences that we can see across generations. There’s a researcher who’s at San Diego State. Her name is Jean Tweng. She’s done most of the work related to this, looking at large-scale epidemiological data sets since we began asking questions of individuals related to these topics, like happiness and well-being. She’s got these large data sets that she looks at.

Jean will even say that the variation within generations is greater than the variation between generations. In the younger generation, they are asking some questions that are legitimate questions about how work fits overall in a life well-lived. As I look at my parents, who were born in the 1930s, or when I look at my older siblings who are Boomers, many of them are asking the same questions, but they may be asking them at a different developmental phase in their lives.

For many of the older generations, it was that you get to work, try things out, muck around, and figure out what it is that’s going to work for you, and then over time, you begin to answer and figure out some of these questions around, “How am I contributing to the greater good?” In the younger generation, they’re asking the same questions, but they’re just asking them earlier. Perhaps that’s because they’ve looked at and learned from the generations that have gone before and said, “Those are great questions. Should I be asking them in my 20s instead of waiting to ask them in my 50s?”

How Positive Psychology Combat Workplace Stress

I want to change gears a little bit. Does happiness and positive psychology combat stress in the workplace? In case you haven’t noticed, work is a four-letter word for a reason. There’s a lot of stress in the workplace. We, as attorneys, see it all the time. Putting that aside, generally speaking, there’s a lot of competition out there, whether it’s for a new customer, a client, a new job, moving up, or what have you. How does what you do and teach combat stress, if it does?

I’m going to preface some comments that I’m going to make around resilience, which is a quality of our ability to navigate and handle times of stress and be able to return to a homeostasis of some sort. There’s stress that goes on in business. My daughter is a triathlete. In order to do what she loves to do most, which is racing, she has to train.

Doing 100 repeats at the track is no fun. She calls it Type 2 fun, the fun that’s not fun. It’s hard work, but she’s doing it in service to something that she believes in or an experience she wants on the other end. Any job is going to have its sources of stress. Even people who feel enormously passionate about their jobs, there is going to be 20% that isn’t fun. That’s something to come to terms with in any organization.

Back to that piece around the stress piece, there is stress that’s the nature of the beast. There’s also perhaps unnecessary or gratuitous stress that gets piled on top. That unnecessary, gratuitous stress often results from some of the structures, design elements, or relationships that we create in the workplace, which can make it an enormously stressful place to work.

I’m always cautious about talking about some of the individual qualities that employees need to cultivate in order to have more resilience. If some of those gratuitous or unnecessary elements of stress have not been given attention, I never want us to fall into the trap of saying, “We don’t need to fix this terrible workplace. You need to do more mindfulness. You need to do a little bit more breathing. You need to toughen up.” Sometimes, that’s not true. We can create profoundly toxic environments, and that does require some attention.

However, work is hard. We are in a competitive environment. Organizations are looking to gain an advantage in the marketplace. The marketplace is changing underneath our feet sometimes minute to minute, let alone year to year. Marty has done some work in this area. They’ve looked at employees who demonstrate the highest level of resilience. There are five different qualities that they tend to demonstrate that are the biggest contributors to their ability to be resilient.

One is emotional regulation, which is their ability to very flexibly and productively manage their own emotions. A sense of optimism, which is that ability to feel confident that you can create a positive future together with your team and work well together. Cognitive agility, which is that ability to think through and work through your mind different scenarios, looking at things from different perspectives, fielding those different perspectives from different members of your team, and then being able to choose among them the one that you think is going to be most productive to taking you into the future.

The last two are related to self-compassion, our own ability to look at our own failures and recognize that there’s some common humanity, and to treat ourselves kindly in those moments where we feel as though we are not necessarily succeeding. All of this is also in service to our ability to build rapport and relationships with the people around us. There is that big asterisk around I never want to tell an employee, “You need to be more emotionally regulated,” when we’ve created this toxic environment around them.

We’re like, “Get yourself together.”

As we take care of our people and the people we serve, we have to orient around our values. Those things cannot be taken away.

As leaders, we have a responsibility to observe, attune, see, intervene, and work with employees to understand how to make changes and how to make things better from a structural or functional standpoint within the organization. The individual characteristics that we bring to the table matter, too. We can help people build some of those characteristics through the ways that we have conversations at work and the training that gets done. Andrew has probably a plethora of ideas that go beyond that, so Andrew, let me turn over to you.

You’ve named all the individual ones that are important and that matter. From an organizational perspective, what do we do to design the conditions? My company is called Eudaimonic by Design for this very reason. We have to think about how we design the conditions where people have a fighting chance at being able to do those things.

The research says there are different things that we can do structurally in an organization. I talked earlier about the importance of giving people a voice and choice. We can think about the ways in which we create the conditions for more participatory decision-making within our organization. We can think about different ways we can give people the opportunity to have flexibility at work. How do we help people manage work-life harmony? How do those things fit together in a better way? What are the ways in which we can make sure that our organizations are fundamentally safe, both physically and psychologically? Work should not be a place that causes harm.

How do we think about things like recognition or career management to give people an opportunity for learning and growth? How do we think about communication, especially as a leader, the important ways in which we are talking about things, naming-wise, and being transparent? How do we think about organizational justice within the organization? We have both procedural and outcome-based justice in terms of the processes that we have, which I know that both of you, as lawyers, would probably completely agree with.

Lastly, how do we create a space where there’s social dialogue, where we’re able to connect, collaborate, and work together effectively? Those are all the kinds of what are sometimes described as virtuous organizational practices, which are very tactical and practical, and are not a huge stretch, but make all the difference in the world so that we aren’t gaslighting people and that we’re not saying, “Here’s a meditation app if you feel stressed.”

I want you to know you both stressed me out very much because I haven’t thought about any of that stuff in the past 30-some-odd years of practicing law. Thank you very much.

Building a Visionary Team

A business owner looks at his or her organization. When do they say to themselves, “I need to talk to one or both of you.” When does a light go off to say to themselves, “I need you.”

Many of the things we’ve talked about here are crisis-related and are related to things not going well in the organization. There are some that come to us and say, “Here are our problems. We have burned-out employees. We’ve got this going on.” There are also some that come to us and say, “We want to build our employees’ well-being because we know that’s going to strengthen us for the future. We don’t have any crises or any problems right now, but we know that if our people are thriving and flourishing, then we as an organization are going to be thriving and flourishing for the future.”

I’ll share that sometimes, leaders can get into roles where you feel very reactionary, and that feels a little bit like your day-to-day work is whack-a-mole. You are waiting for the next person to complain, the next problem that’s going to come up, the next team that’s going to melt down, or what have you. There’s also a way to lead in a manner where you are being more visionary in helping to cultivate and bring along those teams and have conversations about where you’re all headed in the future. That has a strong buffering effect in organizations.

As I said, the vicissitudes of life are going to hit. Look around. You see organizations that are struggling all over. When those moments hit, do you want to have a team that you’ve been holding together with Band-Aids and popsicle sticks, or do you want to have a team that’s thriving, strong, and says, “We got this. We’re ready to go. Let’s stick to our values, and let’s think creatively. We trust in each other. We know that we can handle anything that gets thrown our way.”

That’s a great conversation because it reminds me of when COVID first hit and you had a real crisis moment. How did you react? How did you respond to it?

What we as an organization have focused on is our values, and we’re going to live by those values no matter what. That’s what we can stay firm on and hold firm to. As we take care of our people and as we take care of the people that we serve, it is to orient around those values because those things are stable, and those are things that can’t be taken away.

Wow. That’s all I can say to that.

We deal with business owners in our day-in and day-out activities. That’s one of the reasons Stuart and I started this show. It was to address different issues for business owners. This was a fabulous discussion.

How Leona and Andrew Take Care of Their Well-Being

As we begin to wrap up, because time is getting short, I’m going to ask you both this question. You have busy lives. How do you manage your own well-being, given the fact that this is what you do for a living?

Andrew, do you want to go first?

Sure. They say that all research is research.

Well-being is a whole-body experience. It is not only neck-up.

Great expression. I love it.

Many of us go into the field of positive psychology because we want to be able to answer that question for ourselves. For me, there are two major things that sustain my well-being over time. The first is other people. I am an entrepreneur. I have a small business. I work at home myself. It can be lonely. It can be hard work. It can be very isolating, so I spend a lot of intentional time talking to people, being intentional about who I’m surrounding myself with, and making sure that I have time within my days to make sure that I’m connecting with people that I love.

The other thing that I would say is that physical practice is important. We spend a lot of time as psychology people talking about a neck-up way of thinking about well-being, but everything below is important, too. For me, it is making sure that I have physical practice. My physical practice happens to be yoga. It’s important for me to show up on my mat every day.

Andrew, I’m sitting here chuckling to myself because I was thinking, “Andrew has this way of treating himself in this kinder, gentler way.” I was down in my pain game in the basement on my bike on ROUVY on a threshold workout, grinding, but different strokes for different folks. One way or another, the generalizable piece of that is that well-being is a whole-body experience. Even our emotions are felt somewhere in our bodies. We have a tendency to think of it as neck-up, that it’s all very cognitive, and that our happiness is in our mind, but that’s not true. It is truly a whole body experience.

Andrew, you said the people. For me, I have this extraordinary opportunity where I get to work with amazing thinkers and amazing people who come into our program as students. Through it all, we take these moments to sit back in wonderment when we see these extraordinary people. The everyday goodness is all around us.

When you get curious about people and what they do, it’s gobsmacking what they do in the world and how they contribute to the world. Norman and Stuart, for the two of you, I think about the work that you do. There’s a reason why we call attorneys counselors. When I think about the role that you have in the world in stewarding small businesses and supporting them through probably some of the tougher moments that they have where they’re dealing with negotiations, contracts that are often quite contentious, hard emotions, hard experiences, or hard relationships, the work that you do matters, and it has meaning. People come to you and you afford them relief because of the role that you play as a counselor to them.

This everyday goodness is all around us. I look at you with appreciation for the contributions that you’re making to small business owners. I’ve got several small business owners in my family. From my standpoint, I see how they work and the challenges that they face. It’s so meaningful to have experts like yourselves on their extended team. It matters a great deal.

That, for me, is the wonder that I feel when looking at the unique, different, and very cool people that are all around us all the time. It is incredibly uplifting to me. It’s my moment of awe every year. Every year, before we go into the launch of our next academic year within our program, I sit back in wonderment about all the unique pathways that brought this unique group of people together in that moment and the infinitesimally small chances for that to have happened. It’s pretty incredible.

That was very well said. That’s a great way to conclude this episode.

Episode Wrap-Up and Closing Words

I have to say this has been one of our most fascinating episodes. You brought so much to the table. We appreciate it. All I can say is, “Go Quakers.” Thank you very much.

That brings us to the end of this conversation, one that I hope leaves you feeling both grounded and inspired.

A heartfelt thanks to you, Leona and Andrew, for sharing your wisdom, warmth, and vision for what it means to truly flourish, not just as individuals, but in the systems we live and lead. From the classroom to the boardroom, from coaching to culture design, their work reminds us that well-being isn’t a side dish. It’s a foundation.

As always, thank you for tuning in to the Open For Business. If you haven’t already, be sure to follow the show and leave a review. It helps others discover conversations like this one, which we hope you found valuable.

Until next time, Norman and I want you to stay curious, stay connected, and keep choosing what helps you flourish and be happy.

Everyone, enjoy your weekend. Be safe.

Important Links

- Leona Brandwene

- Eudaimonic by Design

- Leona Brandwene on LinkedIn

- Andrew Soren on LinkedIn

- Be the Sun, Not the Salt

- Eudaimonic by Design on Instagram

- Eudaimonic by Design on Facebook

About Leona Brandwene

Leona Brandwene, MAPP is the Associate Director of Education at the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania. She provides oversight for the Master of Applied Positive Psychology (MAPP) program and the Applied Positive Psychology (APOP) undergraduate certificate, while serving as coordinating instructor for two MAPP courses.

Leona received the 2021 College of Liberal and Professional Studies Award for Distinguished Teaching in Graduate Programs at Penn, as well as UPCEA’s 2021 Excellence in Teaching Award for the Mid-Atlantic Region. She serves on the Council of Advisors of the International Positive Psychology Association (IPPA) and was the 2023 recipient of the Association’s Positive Catalyst Award.

She serves as a scientific advisor for Trellus Health, an organization building resilience among individuals with inflammatory bowel disease, and sits on the board of Shining Light, which leverages positive psychology to build well-being among incarcerated individuals. Previously, she served as a coach and consultant for national healthcare performance improvement initiatives, focusing on reducing preventable infections and enhancing patient safety in acute care settings. Her work also encompassed engaging healthcare organizations in community health efforts and managing comprehensive employee wellness programs to promote workplace well-being.

Leona is currently pursuing a doctorate in education at Penn’s Graduate School of Education. She enjoys cycling, running, serving as a triathlon sherpa, spending time with family, and cheering on her favorite collegiate sports teams—LaSalle women’s triathlon and Alvernia women’s ice hockey. She lives in the Lancaster, PA area with her husband Josh and their daughter Sophie.

About Andrew Soren

Andrew Soren is the Founder and CEO of Eudaimonic by Design, a global network of facilitators, coaches and advisors who share a passion for well-being and believe organizations must be designed to enable it. Together they harness the best of scholarship and years of experience to advise organizations and design systems that unlock potential and bring out the best in people.

For the past 25 years, Andrew has worked with some of the most recognized brands, non-profits and public sector teams to co-create values-based cultures, develop positive leadership, and design systems that empower people to be their best.

He regularly writes and speaks about how to apply the science of wellbeing at work. His most recent article, Meaningful Work, Well-Being, and Health: Enacting a Eudaimonic Vision, was just published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Since 2013, Andrew has been part of the instructional team at the University of Pennsylvania’s internationally renowned Master of Applied Positive Psychology program. He is a member of the board for the International Positive Psychology Association and was Chair of its 8th World Congress on Positive Psychology in 2023.

He was a senior advisor in Governance, Culture, and Leadership at LRN and spent 13 years at BMO Financial Group, one of Canada’s largest banks. There, he led strategy in marketing and human resources, focusing on brand revitalization, leadership development, and the co-creation of high-performance culture.

Andrew is an ICF-certified coach through the Co-Active Training Institute. He is based in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Subscribe Today!